A few weeks ago the Swedish government announced a new AI initiative called the Swedish AI Reform. It's about providing free access to AI tools to Sweden's non-profit and public sector workers. A decent idea, I thought, and my curiosity led me to click through and scope out the onboarding flow.

Having done a lot of GDPR-related work over the years, my attention was naturally drawn to the checkbox about consent for marketing communications. I intentionally left it blank and submitted the form, just to see what it'd do.

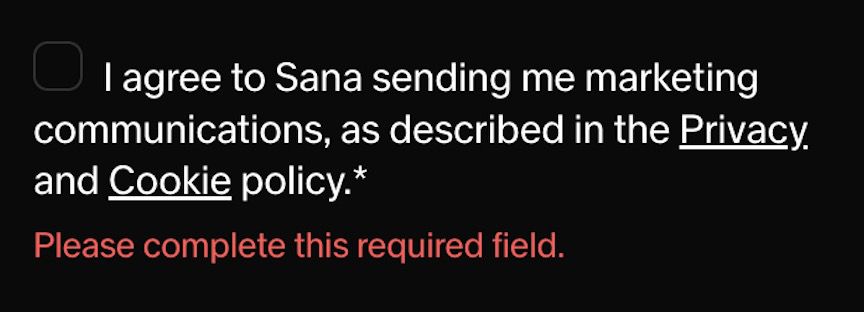

The red validation error means the form submission failed because I hadn't checked the input field to indicate my consent to receive marketing communications. In effect this makes it impossible to sign up for this service without consenting to receive marketing communications. In GDPR nerd parlance this is known as "bundled consent". It's not really allowed, but it's an honest mistake that's easily made if you're operating in a bunch of different jurisdictions and misconfigure something by accident.

It took about ten minutes to file a GPDR complaint with the Swedish Authority for Privacy Protection. From there it took them a couple of weeks to open and process the complaint. They opted to forward the information to the company in question to give them the opportunity to review their GDPR compliance themselves. And just like that, the offending marketing consent checkbox is gone from their signup flow.

Very pleased with this. Nice pragmatic soft-touch approach to enforcement by the Swedish data protection authority matched by the quick, honest fix by the data processor. Great work by all involved and a lovely little success story to show that this legislation is working as intended. Gotta love living in the EU.